Demographics of Turkey

| Demographics of Republic of Turkey | |

|---|---|

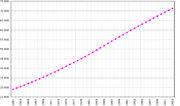

1961–2007 |

|

| Population: | 72,586,256[1] (2009 est.) |

| Growth rate: | 1.45% (2009 est.) |

| Birth rate: | 18.66 births/1,000 population (2009 est.) |

| Death rate: | 6.02 deaths/1,000 population (2008 est.) |

| Life expectancy: | 73.7 years (2009) |

| –male: | 71.5 years (2009) |

| –female: | 76.1 years (2009) |

| Fertility rate: | 1.92 children born/woman (2006 est.) |

| Infant mortality rate: | {{{infant_mortality}}} |

| Age structure: | |

| 0-14 years: | 25.5% (male 9,133,226; female 8,800,070) |

| 15-64 years: | 67.7% (male 24,218,277; female 23,456,761) |

| 65-over: | 6.8% (male 2,198,073; female 2,607,551) (2006 est.) |

| Sex ratio: | |

| At birth: | 1.05 male(s)/female (2006 est.) |

| Under 15: | 1.04 male(s)/female |

| 15-64 years: | 1.03 male(s)/female |

| 65-over: | 0.84 male(s)/female |

| Nationality: | |

| Nationality: | noun: Turk(s) adjective: Turkish |

| Major ethnic: | Turks |

| Minor ethnic: | Abkhazians, Albanians, Arabs, Armenians, Assyrians, Azerbaijanis, Bosniaks, Bulgarians, Chechens, Circassians, Georgians, Greeks, Hamshenis, Jews, Kabardin, Kurds, Laz, Levantines, Ossetians, Pomaks, Roma, and Zazas.[2] |

| Language: | |

| Official: | Turkish |

| Spoken: | Turkish, Kurdish, Laz, Bosnian, Bulgarian, Pontic, Zazaki, Arabic, Azerbaijani, Kabardian, Armenian, Ladino |

This article is about the demographic features of the population of Turkey, including population density, ethnicity, education level, health of the populace, economic status, religious affiliations and other aspects of the population.

As of 2007, the population of Turkey stood at 70.5 million[1] with a growth rate of 1.04% per annum.[3] The Turkish population is relatively young with 25.5% falling within the 0-15 age bracket.[4] There are more than 1 million people of non-Turkish descent, about 1 million of whom are foreign residents.

Contents |

Immigration

Ottoman Empire period

Throughout its history, the Ottoman Empire welcomed altogether hundreds of thousands, maybe millions, of Spanish and Portuguese Jews after 1492; political and confessional refugees from Central Europe: Russian schismatics in 17-18th centuries, Nekrasov Cossacks (after rebellion), Polish and Hungarian revolutionaries after 1848, Jews escaping the pogroms and later the Shoah, White Russians fleeing the Bolshevik Revolution in 1917, Russian and other socialist or communist revolutionaries, Trotskyists fleeing the USSR in the 1930s;

- See also History of the Jews in Ottoman Empire

Republican Period (since 1923)

People moving into Turkey during the Republican Period include Muslim refugees (Muhajir) from formerly Muslim-dominated regions invaded by Christian States, like Crimean Tatars, Circassians and Chechens from the Russian Empire, Algerian followers of Abd-el-Kader, Mahdists from Sudan, Turkmens, Kazakhs, Kyrgyz and other Central Asian Turkic-speaking peoples fleeing the USSR and later the war-torn Afghanistan, Balkan Muslims, either Turkish-speaking or Bosniaks, Pomaks, Albanians, Greek Muslims etc., fleeing either the new Christian states or later the Communist regimes, in Yugoslavia and Bulgaria for instance.

Since the fall of the Iron Curtain, there has been a considerable influx of Eastern Europeans to Turkey, particularly from the former USSR. Some of them have chosen to become Turkish citizens, while others continue to live and work in Turkey as foreigners. The district of Laleli in Istanbul is known with the nickname "Little Russia" due to its large Russian community and the numerous street signs, restaurant names, shop names and hotel names in the Russian language.

Property acquisition since the 1990s

After a change in the Turkish constitution increased foreigners' right to purchase real estate in the country in 2005, a large number of people, mostly pensioners from Western Europe, bought houses in the popular tourist destinations and moved to Turkey. The largest groups, according to the volume of purchases, are the Germans, British, Dutch, Irish, Greeks, Italians and Americans.

Religion

There are no statistics of people's religious beliefs nor is it asked in the census. According to the government, 99.8% of the Turkish population is Muslim, mostly Sunni, some 10 to 20 million are Alevis.[5] The remaining 0.2% is other - mostly Christians and Jews.[6] The Eurobarometer Poll 2005 reported that in a poll 96% of Turkish citizens answered that "they believe there is a God", while 1% responded that "they do not believe there is any sort of spirit, God, or life force".[7] In a Pew Research Center survey, 53% of Turkey's Muslims said that "religion is very important in their lives".[8] Based on the Gallup Poll 2006-08, Turkey was defined as More religious, in which over 63 percent of people believe religion is important.[9][10] According to the Turkish Economic and Social Studies Foundation, 49% of women wear the headscarf or hijab in Turkey.[11][12][13] 33% of male Muslim citizens regularly attend Friday prayers.

Religious groups according to estimates:[5][14]

- Muslim - 99.83% (65-80% Sunni, 20-35% Alevi)

- Christian - 0.13% (70% Armenian Orthodox, 10% Syrian Orthodox, 7% Protestant, 5% Chaldean Catholic, 4% Greek Orthodox, 4% Bulgarian Orthodox)

- Jewish - 0.03% (96% Sephardi, 4% Ashkenazi)

- Bahá'í Faith - 0.01%

The vast majority of the present-day Turkish people are Muslim and the most popular sect is the Hanafite school of Sunni Islam, which was officially espoused by the Ottoman Empire; according to the KONDA Research and Consultancy survey carried out throughout Turkey on 2007[15]:

- 52.8% defined themselves as "a religious person who strives to fulfill religious obligations" (Religious)

- 34.3 % defined themselves as "“a believer who does not fulfill religious obligations" (Not religious).

- 9.7% defined themselves as "a fully devout person fulfilling all religious obligations" (Fully devout).

- 2.3% defined themselves as "someone who does not believe in religious obligations" (Non-believer).

- 0.9% defined themselves as "someone with no religious conviction" (Atheist).

Ethnic groups

The word Turk or Turkish also has a wider meaning in a historical context because, at times, especially in the past, it has been used to refer to all Muslim inhabitants of the Ottoman Empire irrespective of their ethnicity.[16] The question of ethnicity in modern Turkey is a highly debated and difficult issue. Figures published in several different sources prove this difficulty by varying greatly.

It is necessary to take into account all these difficulties and be cautious while evaluating the ethnic groups. A possible list of ethnic groups living in Turkey could be as follows:[17]

- Turkic-speaking peoples: Turkmen, Azeris, Tatars, Karachays, Karakalpaks, Kazakhs, Crimean Tatars, Yörüks, Uyghurs,

- Indo-European-speaking peoples: Kurds, Zazas, Armenians, Hamshenis, Greeks, Bulgarians, Albanians, Pomaks, Macedonians, and Bosniaks

- Semitic-speaking peoples: Arabs, Jews, and Assyrians

- Caucasian-speaking peoples: Georgians, Lazs, Circassians, and Chechens

Proving the difficulty of classifying the ethnicities of the population of Turkey, there are as many classifications as the number of scientific attempts to make these classifications. Turkey is not unique in this respect; many other European countries (e.g. France, Germany) also bear a great ethnic diversity that defies classification. The immense variation observed in the published figures for the percentages of Turkish people living in Turkey (ranging from 75 to 97%) simply reflects differences in the methods used to classify the ethnicities, with a main factor being the choice of whether to exclude or include Kurds. Complicating the matter even more is the fact that the last official and country-wide classification of spoken languages (which do not exactly coincide with ethnic groups) in Turkey was performed in 1965; many of the figures published after that time are very loose estimates.

According to a newspaper, there is a 2008 report prepared for the National Security Council of Turkey by academics of three Turkish universities in eastern Anatolia, there were approximately 60-62 million ethnic Turks, 7,5 million Kurds, 520,000 Zazas, 350,000 Circassians, 70,000 Bosniaks, 300,000 Albanians, 70,000 Georgians, 550,000 Arabs, 300,000 Roma, 300,000 Pomaks, 80,000 Laz, 30,000 Armenians, 24,000 Assyrians, 17,800 Jews, and 2,000 Greeks living in Turkey.[18]

Turks

The Oğuz people (western branch of the wider Turkic peoples) began arriving in the region as mercenary soldiers under the Abassid caliphs over a thousand years ago. Their origins were in the Altay region (across the boundary of modern day Kazakhstan, Russia, Mongolia and China). The Oghuz became substantially mixed during their westward migrations, with Persians, Armenians and other Caucasian peoples.

The Oğuz people, which once constituted the majority of the reigning fraction of Turkic people in Anatolia, gained political, cultural and military dominance in the region but remained for centuries only a small part of the population, demographically speaking. Anatolia, which was formerly a part of many civilizations like the Hittites and the Byzantine Empire, was (and still is) an ethnically very mixed region where the last official religion was Greek Orthodox, but there are also adherents of other Christian churches or "deviant" Christian or syncretist movements, as well as Jews.

The Turkic migrations were not only westwards, but also south into India, China and Afghanistan, north into Siberia and east into Korea (although some sources contest this). The wider Turkic peoples therefore represent one of the most widely distributed ethnicities in the world. Other non-Ottoman Turkic tribes are present in Turkey and include the Karakalpaks, Turkmens, Kazakhs, Kumyks, Uzbeks, Tatars, Azeris, Balkars, Uyghurs, Karachays, Nogai and Kyrgyz, mostly the result of modern migrations from the former Soviet Union.

Pontians

Please update. no mention of Asia minor Greeks along the black sea coast. Usually referred to as Rumcha in Turkish. There are still up to 300,000 people speaking this ancient dialect, in Turkey today. But for fears of reprisals from certain sects they chose to speak it at home only.

Arabs

Armenians

Armenians in Turkey have an estimated population of 40,000 (1995) to 70,000.[19][20] Most are concentrated around Istanbul. The Armenians support their own newspapers and schools. The majority belong to the Armenian Apostolic faith, with smaller numbers of Armenian Catholics and Armenian Evangelicals.

Kurds

The Kurdish identity remains the strongest of the many minorities in modern Turkey. This is perhaps due to the mountainous terrain of the south-east of the country, where they predominate and perhaps represent a majority. They inhabit all major towns and cities across Turkey, however. No accurate up-to-date figures are available for the Kurdish population, because the Turkish government has outlawed ethnic or racial censuses. Though some estimates such as the CIA World Factbook place their population at approximately 18%.[21] Another estimate, according to Ibrahim Sirkeci, an ethnic Turk, in his book The Environment of Insecurity in Turkey and the Emigration of Turkish Kurds to Germany, based on the 1990 Turkish Census and 1993 Turkish Demographic Health Survey, is 17.8%.[22]

The Minority Rights Group report of 1985 (by Martin Short and Anthony McDermott) gave an estimate of 15% Kurds in the population of Turkey in 1980, i.e. 8,455,000 out of 44,500,000, with the preceding comment 'Nothing, apart from the actual 'borders' of Kurdistan, generates as much heat in the Kurdish question as the estimate of the Kurdish population. Kurdish nationalists are tempted to exaggerate it, and governments of the region to understate it. In Turkey only those Kurds who do not speak Turkish are officially counted for census purposes as Kurds, yielding a very low figure.'. In Turkey: A Country Study, a 1995 on-line publication of the U.S. Library of Congress, there is a whole chapter about Kurds in Turkey where it is stated that 'Turkey's censuses do not list Kurds as a separate ethnic group. Consequently, there are no reliable data on their total numbers. In 1995 estimates of the number of Kurds in Turkey ranged from 13 million to 15 million.' out of 61.2 million, which means from 17% to 25%. Kurdish national identity is far from being limited to the Kurmanji language community, as many Kurds whose parents migrated towards Istanbul or other large non-Kurdish cities mostly speak Turkish, which is one of the languages used by the Kurdish nationalist publications.

Assyrians

An estimated 25,000 Assyrians live in Turkey, with about 17,000 in Istanbul and the other 8,000 scattered in southeast Turkey. Mass migration occurred after World War II because of the Assyrian genocide. They belong to the Syriac Orthodox Church, Syriac Catholic Church, and Chaldean Catholic Church. The Mhallami, who usually are described as Arabs, have Assyrian ancestry. They live in the area between Mardin and Midyat, called in Syriac "I Mhalmayto" (ܗܝ ܡܚܠܡܝܬܐ).

Circassians

Towards the end of the Russian-Circassian War (1763–1864) many Circassians fled their homelands in the Caucasus and settled in the Ottoman Empire.

Lazs

Most Lazs today live in Turkey, but the Laz minority group has no official status in Turkey. Their number today is estimated to be around 500,000.[23] and 1.5 million[24][25] Most of the Laz are Sunni Muslims. They are typically bilingual in Turkish and their native Laz language, which belongs to the South Caucasian group. The number of the Laz speakers is decreasing, however, and is now limited chiefly to the Rize and Artvin areas. The historical term Lazistan — formerly referring to a narrow tract of land along the Black Sea inhabited by the Laz as well as by several other ethnic groups — has been banned from official use and replaced with Doğu Karadeniz (which also includes Trabzon). During the Russo-Turkish War of 1877–1878, the Muslim population of Russia near the war zones was subjected to ethnic cleansing; many Lazs living in Georgia fled to the Ottoman Empire, settling along the southern Black Sea coast to the east of Samsun.

Roma people

The Roma in Turkey descend from the times of the Byzantine Empire. There are officially about 500,000 Roma in Turkey,[26][27][28] though the unofficial estimations of experts doesn't agree with this number. Sulukule, located in Western Istanbul, is the oldest Roma settlement in Europe.

Converts from Christianity and Judaism

Islam spread slowly over many generations either through voluntary or forced conversions; many poor families chose to become Muslims in order to escape a special tax levied on conquered millet peoples or for reasons of upward mobility. Another common motivation was to escape the devşirme system for recruiting Janissaries to the Ottoman forces, and the similar institution of using dhimmi children to serve as odalisques or köçeks in the Ottoman harems or as tellaks in the hammams. Conversion to Islam was usually accompanied by the adoption of the Ottoman-Turkish language and identity and eventual acceptance into the mainstream population, because conversion was generally irreversible and resulted in ostracism from the original ethnic group.

While smaller converted groups generally assimilated to the culturally dominant Turkish ethnicity, some have maintained a distinct ethnicity for centuries. The Hamshenis are an ethnic group of (originally) Armenians who converted to Islam in the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries but still keep some pre-Islamic traditions and retain the use of two distinct Armenian dialects. Their Laz neighbours name them "Sumekhi" the Turkish term for Armenians. There are also some Pontic Greek Muslims.

Among the Black Sea Turkish intellectuals, there has been in the last few years a revival of interest for the forgotten ethnic and religious identities of their ancestors. The research by Özhan Öztürk, but also the books of Ömer Asan and Selma Koçiva, are good illustrations at this trend.

There have also been, through the 19th and 20th centuries and still nowadays, rumors of the existence, mostly in rural and small town areas, of sizable populations of Crypto-Christians and Crypto-Jews, notably among the Dönme, descendants of Sabbatai Zevi's followers who had to convert en masse following Zevi's example.

Languages spoken

Turkish (official), Kurdish, Circassian, Zazaki, Arabic, Azeri, Armenian, Syriac, Bulgarian, Albanian, Laz, Georgian, Greek, and Bosnian.

| Language | Mother tongue | Only language spoken | Second best language spoken |

|---|---|---|---|

| Abaza | 4,563 | 280 | 7,556 |

| Albanian | 12,832 | 1,075 | 39,613 |

| Arabic | 365,340 | 189,134 | 167,924 |

| Armenian | 33,094 | 1,022 | 22,260 |

| Bosnian | 17,627 | 2,345 | 34,892 |

| Bulgarian | 4,088 | 350 | 46,742 |

| Bulgarian - Pomak | 23,138 | 2,776 | 34,234 |

| Circassian | 58,339 | 6,409 | 48,621 |

| Croatian | 45 | 1 | 1,585 |

| Czech | 168 | 25 | 76 |

| Dutch (or Flemish) | 366 | 23 | 219 |

| English | 27,841 | 21,766 | 139,867 |

| French | 3,302 | 398 | 96,879 |

| Georgian | 34,330 | 4,042 | 44,934 |

| German | 4,901 | 790 | 35,704 |

| Greek | 48,096 | 3,203 | 78,941 |

| Italian | 2,926 | 267 | 3,861 |

| Kurdish (Kurmanji) | 2,219,502 | 1,323,690 | 429,168 |

| Judæo-Spanish | 9,981 | 283 | 3,510 |

| Laz | 26,007 | 3,943 | 55,158 |

| Persian | 948 | 72 | 2,103 |

| Polish | 110 | 20 | 377 |

| Portuguese | 52 | 5 | 3,233 |

| Romanian | 406 | 53 | 6,909 |

| Russian | 1,088 | 284 | 4,530 |

| Serbian | 6,599 | 776 | 58,802 |

| Spanish | 2,791 | 138 | 4,297 |

| Turkish | 28,289,680 | 26,925,649 | 1,387,139 |

| Zaza | 150,644 | 92,288 | 20,413 |

Languages spoken in Turkey, 1984 data[29]

Literacy

Education is compulsory and free from ages 6 to 15. The literacy rate is 95.3% for men and 79.6% for women, for an overall average of 87.4%.[30]

Life expectancy

According to statistics released by the government in 2005, life expectancy stands at 68.9 years for men and 73.8 years for women, for an overall average of 71.3 years for the populace as a whole.

Minorities

Modern Turkey was founded by Mustafa Kemal as secular (Laiklik, Turkish adaptation of French Laïcité), i.e. without a state religion, or separate ethnic divisions/ identities.

The concept of "minorities" has only been accepted by the Republic of Turkey as defined by the Treaty of Lausanne of 1924 and thence strictly limited to Greeks, Jews and Armenians, only on religious matters, excluding from the scope of the concept the ethnic identities of these minorities as of others such as the Kurds who make up 15% of the country; others include Christian Assyrians of various denominations, Alevis and all the others.

There are many reports from sources such as (Human Rights Watch, European Parliament, European Commission, national parliaments in EU member states, Amnesty International etc.) on persistent yet declining discrimination.

Certain current trends are:

- Turkish imams get salaries from the state (like Greek Orthodox clerics in Greece), whereas Turkish Alevi as well as non-Orthodox and non-Armenian clerics are not paid

- Imams can be trained freely at the numerous religious schools and theology departments of universities throughout the country; minority religions can not re-open schools for training of their local clerics due to legislation and international treaties dating back to the end of Turkish War of Independence. The closing of the Theological School of Halki is a sore bone of contention between Turkey and the Eastern Orthodox world.;

- The Turkish state sends out paid imams, working under authority from the Presidency of Religious Affairs (Diyanet İşleri Başkanlığı) to various European or Asian countries with Turkish- or Turkic-speaking populations, with as local heads officials from the Turkish consulates;

- Turkey has recently engaged in promulgating a series of legal enactments aiming at removal of the procedural hurdles before the use of several local languages spoken by Turkish citizens such as Kurdish (Kurmanji), Arabic and Zaza as medium of public communication, together with several other smaller ethnic group languages. A few private Kurdish teaching centers have recently been allowed to open. Kurdish language TV broadcasts on 7/24 basis at the public frequency denominated as the 6th channel of the government-owned Turkish Radio and Television Institution TRT-6; TRT Şeş (six in Kurdish), while the private national channels show no interest yet. However there are already several satellite Kurdish TV stations operating from Kurdish Autonomous Region at Northern Iraq and Western Europe, broadcasting in Kurdish, Turkish and Neo-Aramaic languages, Kurdistan TV, KurdSAT, etc.;

- Non-Muslim minority numbers are said to be falling rapidly, mainly as a result of aging, migration (to Israel, Greece, the United States and Western Europe).

- There is concern over the future of the Greek Orthodox Patriarchate, which suffers from a lack of trained clergy due to the closure of the Halki school. The state does not recognise the Ecumenical status of the Patriarch of Constantinople.

According to figures released by the Foreign Ministry in December 2008, there are 89,000 Turkish citizens designated as belonging to a minority, two thirds of Armenian descent.[31]

External links

References

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 Official census-based estimate per December 31, 2009

- ↑ Within the defition established and internationally agreed in the 1923 Lausanne Treaty, three minority groups are officially recognized in Turkey, namely Armenians, Greeks and Jews.

- ↑ http://www.worldbank.org.tr/WBSITE/EXTERNAL/COUNTRIES/ECAEXT/TURKEYEXTN/0,,menuPK:361738~pagePK:141132~piPK:141109~theSitePK:361712,00.html

- ↑ "Turkey - Population and Demographics". Intute. 2006-07. http://www.intute.ac.uk/sciences/worldguide/html/1046_people.html. Retrieved 2006-12-10.

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 Shankland, David (2003). The Alevis in Turkey: The Emergence of a Secular Islamic Tradition. Routledge (UK). ISBN 0-7007-1606-8. http://books.google.com/?id=lFFRzTqLp6AC&pg=PP1&lpg=PP1&dq=Religion+in+Turkey.

- ↑ "CIA World Factbook". CIA. December 2007. https://www.cia.gov/library/publications/the-world-factbook/geos/tu.html. Retrieved 2007-12-17.

- ↑ "Eurobarometer on Social Values, Science and technology 2005" (PDF). Eurobarometer. http://ec.europa.eu/public_opinion/archives/ebs/ebs_225_report_en.pdf. Retrieved 2007-12-18.

- ↑ Richard Wike and Juliana Menasce Horowitz. "Lebanon's Muslims: Relatively Secular and Pro-Christian". Pew Global Attitudes Project. http://pewresearch.org/pubs/41/lebanons-muslims-relatively-secular-and-pro-christian.

- ↑ 2009 Gallup poll Gallup Poll

- ↑ Gallup World View

- ↑ Lamb, Christina (2007-04-23). "Head scarves to topple secular Turkey?". London. http://www.timesonline.co.uk/tol/news/world/middle_east/article1752230.ece.

- ↑ "Headscarf war threatens to split Turkey". Times Online (London). 2007-05-06. http://www.timesonline.co.uk/tol/news/world/middle_east/article1752230.ece.

- ↑ Clark-Flory, Tracy (2007-04-23). "Head scarves to topple secular Turkey?". Salon.com. http://www.salon.com/mwt/broadsheet/2007/04/23/headscarf/. Retrieved 2008-08-04.

- ↑ Religious Freedom Report U.S. Department of State. Retrieved on 2009-09-15.

- ↑ KONDA Research and Consultancy (2007-09-08). "Religion, Secularism and the Veil in daily life" (PDF). Milliyet. http://www.konda.com.tr/html/dosyalar/ghdl&t_en.pdf.

- ↑ American Heritage Dictionary (2000). "The American Heritage Dictionary of the English Language: Fourth Edition - "Turk"". Houghton Mifflin Company. http://www.bartleby.com/61/92/T0419200.html. Retrieved 2006-12-27.

- ↑ Andrews, Peter A. Ethnic groups in the Republic of Turkey., Beiheft Nr. B 60, Tübinger Atlas des Vorderen Orients, Wiesbaden: Reichert Publications, 1989, ISBN 3-89500-297-6 ; + 2nd enlarged edition in 2 vols., 2002, ISBN 3-89500-229-1

- ↑ "Türkiyedeki Kürtlerin Sayısı!" (in Turkish). Milliyet. 2008-06-06. http://www.milliyet.com.tr/default.aspx?aType=SonDakika&Kategori=yasam&ArticleID=873452&Date=07.06.2008. Retrieved 2008-06-07.

- ↑ Turay, Anna. "Tarihte Ermeniler". Bolsohays: Istanbul Armenians. http://www.bolsohays.com/webac.asp?referans=1. Retrieved 2007-01-04.

- ↑ Hür, Ayşe (2008-08-31). "Türk Ermenisiz, Ermeni Türksüz olmaz!" (in Turkish). Taraf. http://www.taraf.com.tr/Yazar.asp?id=12. Retrieved 2008-09-02. "Sonunda nüfuslarını 70 bine indirmeyi başardık."

- ↑ "CIA — The World Factbook". CIA. https://www.cia.gov/library/publications/the-world-factbook/geos/tu.html. Retrieved 2006-03-11.

- ↑ Sirkeci, Ibrahim (2006). The Environment of Insecurity in Turkey and the Emigration of Turkish Kurds to Germany. New York: Edwin Mellen Press. pp. 117–118. ISBN 978-0-7734-5739-3. http://www.mellenpress.com/mellenpress.cfm?bookid=6794&pc=9. Retrieved 2006-08-11.

- ↑ Kjeilen, Tore. "Turkey: Religions & Peoples". LookLex Encyclopedia. http://i-cias.com/e.o/turkey_4.htm.

- ↑ Minority Rights Group International : Turkey : Laz

- ↑ http://www.geocities.com/Athens/9479/laz.html

- ↑ http://www.unhcr.org/refworld/topic,4565c2253b,4677ea9b2,46ef87ab32,0.html

- ↑ http://www.eurasianet.org/departments/civilsociety/articles/eav072205.shtml

- ↑ http://www.ihf-hr.org/viewbinary/viewdocument.php?doc_id=7081

- ↑ Heinz Kloss & Grant McConnel, Linguistic composition of the nations of the world, vol,5, Europe and USSR, Québec, Presses de l'Université Laval, 1984, ISBN 2-7637-7044-4

- ↑ Turkish Statistical Institute (2004-10-18). "Population and Development Indicators - Population and education". Turkish Statistical Institute. http://nkg.die.gov.tr/en/goster.asp?aile=3. Retrieved 2006-12-11.

- ↑ "Foreign Ministry: 89,000 minorities live in Turkey". Today's Zaman. 2008-12-15. http://www.todayszaman.com/tz-web/detaylar.do?load=detay&link=161291. Retrieved 2008-12-15.

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||